Algorithms¶

Big O Notation¶

https://justin.abrah.ms/computer-science/big-o-notation-explained.html

O(n), O(n^2), and O(1)¶

A function(algorithm)’s Big-O notation is determined by how it responds to different inputs. How much slower is it if we give it a list of 1000 things to work on instead of a list of 1 thing?

Let’s give an example:

- def is_myitem_in_list(myitem, the_list):

- for item in the_list:

- if myitem == item:

- return True

return False

So if we call this function like is_myitem_in_list(1, [1,2,3]), we loop over our list looking for 1. Should be pretty fast. If we change to is_myitem_in_list(“potato”, [1,2,3]) then we have our worst possible runtime - it has to go through all list values before it returns False.

From the looks of it, in the worst case scenario, the for loop will run a maximum of len(the_list) times. Since Big-O notation measures the worst cast run time of an algorithm (function), the Big-O notation of this function is O(n), roughly meaning that the number of inputs has a linear relationship with how long it’s going to take to run. If you graphed it out where x=num_inputs and y=time_taken, you’d get a nice linear graph. The assumption here is that every item in your input list takes the same amount of time to process.

So what about this function:

- def is_none(item):

- return item is None

This is a bit contrived...but it serves as a good example of an O(1) function, also called constant time. What it means is no matter how big our input, it always takes the same amount of time to compute things. You could pass it a million integers and it will take the same amount of time to process as if you passed a single integer. Constant time is the best case scenario for a function.

Another example:

- def all_combinations(the_list):

results = [] for item in the_list:

- for item_again in the_list:

- results.append((item, item_again))

return results

This matches every item in the list with every other item in the list. For example, if we passed in [1,2,3], we’d get back [(1,1),(1,2),(1,3),(2,1),(2,2),(2,3),(3,1),(3,2),(3,3)]. You could use this idea to brute force a PIN number. This is part of the field of combinatorics. The above algorithm is considered O(n^2) because for every item in the list (aka n for input size), we have to do n more operations. So n * n == n^2.

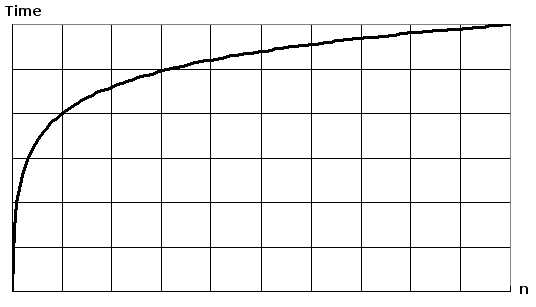

Referring back to Figure 1, as we add input items, we can see quadratic growth.

O(log n)¶

O(log n) basically means that time goes up linearly while the n goes up exponentially. So if it takes 1 second to compute 10 elements, it will take 2 seconds to compute 100 elements, 3 seconds to compute 1000 elements, and so on. Remember again that big-O is stating worst case, so it’s more accurate to say that the running time of an O(log n) (or any other big-O) grows at most proportional to “log n”.

Divide-and-conquer type algorithms are typically O(log n) - for example binary search and part of quick sort. More detail about these algorithms later, but a quick example of an O(log n) operation would be looking up someone in a phone book. You first open up the middle of the book, and since it is sorted alphabetically, you can immediately discard half the book from your search since you may be at letter “K” and the person you are looking up has a last name starting with the letter “R”. You’ve just narrowed your search to the final half of the book. You then open halfway the remaining half of the book, and continue doing this until you get to the R’s, then the Ri’s, then the Ric’s, and so on. With each guess, your search range is cut in half (or more, if you are predicting the number of pages between letters). Read about binary search later on this page for a better understanding.

Calculatink Big-O¶

Just follow your code!

- def count_ones(a_list):

total = 0 for element in a_list:

- if element == 1:

- total += 1

return total

- First, we’re setting total to 0. We’re writing out a chunk of memory, passing in a value and not operating on that value in any way. This is an O(1) operation.

- Next, we’re doing a loop. Each item in a_list is done once (worst case). As we add more input values, the time it takes to get through the loop increases linearly. We use a variable to represent the size of the input, which everyone calls n. So, the “loop over a list” function is O(n) where n represents the size of a_list.

- Next, we check whether an element is equal to 1. This is a binary comparison - it happens once. “element” could be 8, [1,2,3,4,9], or a binary blob, it makes no difference to the comparison, it happens once. This is an O(1) operation.

- Next we add 1 to total. This is the same as setting total to zero, except a read happens first and addition happens. Addition of one, like equality, is constant time. O(1)

- So now we have O(1)+O(n) * (O(1)+O(1)). This reduces to 1+n*2, or O(1)+O(2n). In big O, we only care about the biggest “term”, where “term” is a portion of the algebraic statement, so we’re left with O(2n).

- Since big O only cares about approximation, 2n and n are not fundamentally different - they are simply greater or lesser grades on a linear graph. For example, (1,1),(2,2),(3,3) and (1,2),(2,4),(3,6) is still a linear increase in runtime. Because of this, we can say O(2n) is O(n)

- To sum it up, the answer is that this function has an O(n) runtime (or a linear runtime). It runs slower the more things you give it, but should grow at a predictable rate.

Sorting Algorithms¶

Write about python’s default, timsort. ref: http://corte.si//posts/code/timsort/index.html